We are all aware that the heating of the Earth caused by greenhouse-gas emissions will have myriad horrifying consequences. And the same bonanza of coal, oil, and gas that produced most of those emissions has also enabled and amplified the industrial world’s transgression of most other critical planetary boundaries: biodiversity loss, soil degradation, disruption of the Earth’s nitrogen cycle, and others.

This was illustrated by a study published in 2020 by a group of Israeli scientists, finding that our species has reached a grim milestone. As recently as 1980, the total weight of all human-made objects and structures on Earth had grown to equal about one-fourth of the total weight of all living terrestrial biomass. That in itself is astonishing. But the accumulation of human-produced mass has accelerated over the past four decades, to the point of overtaking and now surpassing the Earth’s total biomass. The authors of the study calculated further that “on average, for each person on the globe, anthropogenic mass equal to more than his or her bodyweight is produced every week.” Every week!

Such overproduction cannot continue. Both the flow of material resources going into society’s industrial pipeline and the flow of products and wastes coming out the other end are accelerating the degradation of Earth systems. A focus on reducing waste is not enough; the problem must be dealt with at the point of production, to deeply reduce the quantities of materials and energy going into the economic pipeline, if we are to reduce the overall damage. Therefore, if the transgression of all planetary boundaries is to be stopped and reversed, it is the extraction of material and energy resources, along with other forms of ecological destruction, that must be tightly restrained. And markets have no power to do that.

Ration? Why ration?

Since the 1970s, efforts to limit society’s aggregate ecological footprint by encouraging lifestyle changes and voluntary restraint in consumption have failed time and time again. Even most of the people who recognize the need to cut back are not going to do so themselves when they know that the great majority of people are going to keep consuming up to the limits set by their income and wealth. To reduce resource use on the scale required today, more dramatic measures are needed, including strict limits on total energy and material use society-wide, and, for consumers, compulsory rationing.

The need for rationing has become clear in this hot summer of 2022, with military conflict and supply-chain disruption having driven energy supplies down even as extreme weather has driven energy demand, and therefore prices, to record heights. Governments in California, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere have launched campaigns aimed at limiting consumers’ use of air conditioning, appliances, and car charging. This has depended so far on calls for voluntary restraint, as a way of averting the need for involuntary restraint in the form of rolling electricity blackouts. Such exhortations can help get a society through a short-term mismatch of supply and demand, but to permanently reduce consumption, mandatory rationing with uniform limits is required to ensure sufficiency and fairness.

There has long been interest in a carbon tax as an alternative to rationing of resource use. If we were living in 1990, with half a century ahead of us in which to rein in ecological destruction, some market-based mechanisms might help reduce resource extraction and material production. But it’s too late now, even if we try to steer the market with taxes, largely because demand for essential goods, and especially energy, is highly price-inelastic. And a carbon tax, which will rise as time passes, also puts the greatest burden on low-income households, even if there is an equal-shares rebate of the tax revenue. If we did want to hold global warming below the safe limit of 1.5°C, IPCC estimates, a carbon tax would need to start now at $250 to $1,000 per ton and rise as high as $27,000 per ton by the year 2100. By comparison, prices in today’s carbon markets are comically small: $6 in the European system and $3 for Japan’s carbon tax.

Economic modelers are finding more and more that what they view as an acceptable carbon price would deliver disturbingly large increases in global temperatures. The Nobel-winning economist William Nordhaus, a pioneer of such analyses, has concluded that even the kinds of tax policies that would limit warming only weakly—allowing a dangerous 2.5°C increase over pre-industrial levels—would be too hard on the economy; in his words, they would be “unrealistically ambitious” and “strain credulity.” The economically “rational” goal, he estimated, would be a cataclysmic temperature rise of 3.5°.

It’s too late to sufficiently reduce humanity’s ecological footprint by focusing policy at the point of consumption. It now must focus on the point of extraction and production. Societies must find a direct, secure way to limit the quantities of fuels and minerals, and other resources they extract from the Earth’s crust and use to produce material goods.

That will trigger a need for collective decisions on how to allocate and use resources to serve basic human needs. Even then, production of some goods won’t be sufficient to satisfy unrestrained demand, and shortages will result. For the sake of justice and equity, rationing will become essential.

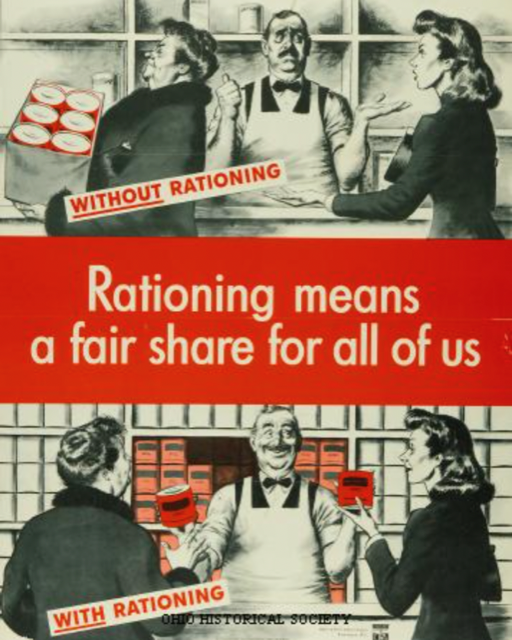

Rationing happens all the time. The most familiar version is rationing by ability-to-pay. There’s also the first-come-first-served principle, a.k.a. rationing-by-queuing. But when shortages arise, allocating resources or goods on the basis of equal shares per person, per household, etc., is the fairest way to ration. In this, the goal of rationing is too often misunderstood. It is best used not as the primary means of reducing consumption, but rather as an adaptation to existing shortages, whether they’re externally triggered or self-imposed. Fair-shares rationing of essential goods and services, with price controls, can ensure sufficient and equitable access for everyone.

When deployed effectively, rationing comes at the end of a series of responses to limited supply. To sustain production of essential goods, governments may need to allocate scarce resources toward essential production and bar their use in wasteful or superfluous production. This was done in the United States during World War II by the War Production Board and then in a limited way on several later occasions through invocation of the Korean War-era Defense Production Act—most recently during the coronavirus pandemic. But even with planned allocation of scarce resources, production of essential consumer goods may not be able to keep pace with unrestrained demand. In a free market, that would ignite inflation; therefore, price controls would be needed to keep goods affordable. But without a means of holding down demand, controlled prices could stimulate even higher demand, pitting consumer against consumer with gravely unjust results, including rationing-by-queueing. The endless lines at gas stations in the 1970s are emblematic of what happens when you have price controls without demand control. In such situations, the most reliable means of ensuring that every household has access to a sufficient, fair share is rationing.

Organized rationing of scarce essential goods by quantity rather than price is practiced in many ways around the world. Many American homeowners have become accustomed to lawn-watering or car-washing being limited to certain days of the week or times of day in times of drought. In impoverished neighborhoods of Mumbai and other Indian cities, potable city water may run from taps for as little as a half-hour per day, on a rotating schedule. Farmers around the world have worked out elaborate systems for equitably rationing irrigation water. Low-income families in many countries (including Egypt, India, and, yes, the United States) are eligible for ration cards that provide for purchase of subsidized food up to specified limits. When demand for electricity exceeds supply, power companies typically ration through rolling blackouts. Much grimmer cases of rationing involve medical care. The Covid-19 pandemic spurred triage-style rationing of ventilators, treatments, and even admission to hospitals. The UK National Health Service and other universal health care systems have long rationed services in various ways. Medical rationing has always been extremely controversial.

Consumption is strongly correlated with wealth or income, so rationing requires the affluent to make the biggest sacrifices. Lower-income households can even find themselves better off under a system of price controls and rationing. During World War II, low-income households ate much better than they had before the war. Nationwide, per-capita consumption of protein, calories, calcium, and vitamins all increased.

If we leave health care aside, other forms of rationing scarce goods tend to garner widespread support, thanks to their egalitarian nature. Food-ration programs have always been highly popular wherever they are deployed. People usually accept and readily adapt to water rationing. In August 1942, early in the war when only limited numbers of items were being rationed in the United States, a poll found 70 percent of respondents feeling they had not yet been asked to sacrifice enough. Six months later, with controls starting to tighten, 60 percent of respondents to a Gallup poll still felt the government should have acted faster and more decisively in rationing scarce goods.

Even with rationing at its height in the 1943–45 period, polls consistently found strong approval, often in the range of two to one.

Allocation and rationing efforts of the past and present are ad-hoc responses to unavoidable resource scarcity, and measures are typically applied commodity by commodity, as they were in the 1940s. Now, with a global ecological emergency underway, we are confronted with the need to limit extraction and use of virtually all resources—intentionally, as a society. This is a dizzyingly complex problem, so where do we begin, and with which resources?

I have been arguing for some time that we start by rapidly phasing out oil, gas, and coal. Unlike other resources, fossil fuels must be almost completely purged from our economies in coming years if Earth is to avoid catastrophic heating. We have to snuff out the burning of fossil fuels—the beating heart of global capitalism—faster than we are able to phase in alternative energy sources to replace them. For the Earth, this is an opportunity. Capping and rapidly reducing fossil fuel extraction will reduce the energy available to industry for production of virtually all goods. That will mean less exploitation of mineral and biological resources and less production of plastic and other wastes.

A fossil fuel cap would not substitute for other conservation measures or rights-of- nature laws. More logging bans would be needed, for example, to prevent increased use of wood as a substitute for coal. Water rationing, almost always a local issue, would need to continue where needed. Biodiversity would continue to require protection whether or not global warming is curbed. But to get us started, at long last, on the road to global ecological restraint, a declining cap on fossil fuel extraction and use is an essential first step. Adaptation would then come through planned allocation of energy resources to essential industries, along with rationing to ensure fairness and sufficiency for energy consumers.

Cap and Adapt

Starting about six years ago with a New Republic article by Bill McKibben and a plank in the 2016 Democratic Party platform, there have been numerous calls for America to mount a “World War II-style” mobilization to address the climate emergency.

Advocates typically point to the rapid scale-up of industrial output to support that monumental war effort as a model for rapid production and deployment of renewable energy capacity and infrastructure today. In contrast, I argue that the far more important lesson of the 1940s was the transformation of the U.S. civilian economy, almost overnight, in order to deal with short supplies. The shortages were caused partly by loss of imports but also by diversion of the bulk of the nation’s resources toward production of ships, tanks, armaments, sustenance for troops, etc. Planned allocation of energy and other resources, price controls, and consumer rationing were central to that wartime transformation. They would also be our key to our own adaptation if the nation succeeds in suppressing the supply of fossil fuels while at the same time diverting a big share of the remaining fuel supplies into production of renewable energy capacity and conservation efforts.

In 2020, my colleague Larry Edwards and I published a proposal called “Cap and Adapt” aimed at limiting, allocating, and rationing fossil energy. I’ll briefly discuss the main points here. The first, most crucial policy is to place impervious caps on the nation’s total supplies of oil, natural gas, and coal. These caps have nothing to do with the largely discredited cap-and-trade strategy that has been used in Europe and elsewhere. These caps would be leakproof, with no waivers, workarounds, offsets, or other gimmickry. Most importantly, they would ratchet down quickly, year by year, toward zero.

The fossil-fuel industries would want nothing to do with such an arrangement, so they and their resource reserves would probably have to be nationalized and managed by public cooperatives. Each year, the cooperatives would be issued free permits that allow them to extract and distribute specified quantities of the three fossil fuels. The permits would be denominated not in carbon units or dollars but in barrels of oil, cubic feet of gas, or tons of coal. Fewer permits would be issued with each passing year as the cap ratchets down. To keep the cap hermetically sealed, imports and exports of all three fuels would be banned.

The public cooperatives would allocate their diminishing allotments of fuels to society’s various sectors, giving priority to renewable energy manufacturing and installation; critical consumption, as in home heating; and essential uses in agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation. The co-ops would apportion supplies of fossil fuels among local utilities to maintain adequate power generation, filling gaps not yet being filled by expanding non-fossil sources.

Fair-shares rationing would be needed in the consumer energy market. Each household could have an account, analogous to a bank account but not involving money, into which ration credits would be deposited, with equal quantities per household. The credits would be deducted from the ration account via a debit-type card, primarily when buying vehicle fuel or paying utility bills, but also when booking air travel or other high fuel-consuming activities. Energy-frugal households could either save their unused credits for future use or sell them into a ration pool from which they could be equitably distributed to households that require additional credits. Redistribution of credits from the unused pool could be carried out, for example, by locally organized cooperatives operating under principles of equity and deliberative democracy. Although every community would be playing by the same national rules, greater local autonomy could be achieved by designating a supplemental pool of collective energy rations to be allocated by the community as a whole for the common good.*

As the total fuel supply tightens and a renewable energy system is still being developed, energy allocation among industries is unlikely be sufficient for them to meet unrestrained demand for essential goods. Ad hoc rationing with price controls could become necessary not only for energy but also for material goods. This is another example of rationing in its proper role, as an adaptation to agreed-upon limits.

Ecological degradation can be curtailed by capping production, but not by only rationing consumption. Rationing, however, can ensure sufficiency and equity.

Restraint Is Still Possible

It’s time to confess that I am not an economist (and you can draw your conclusions from that, whether negative or positive). That’s why, in the process of writing a book on rationing a decade ago, I got in touch with a couple of economists whose past work I was relying upon, to clarify some points. Among other things, I asked them if, considering the predicament we are facing in this hot new century, they could foresee a role for rationing in climate mitigation and adaptation. Hugh Rockoff, who had written a definitive 1984 history of price controls and rationing in the United States, said he believed that, today, in the wake of climatic disasters, federal agencies “should be prepared to move in with food and fuel, and a rationing system whenever they are needed,” but that was about the extent of it. He did not foresee rationing being used ever again except as a short-term crisis management tool.

The other economist I contacted, Martin Weitzman, had developed some of the basic theory of rationing. In a theoretical paper published during the energy crisis of the 1970s (free pdf of an early draft manuscript here), he had thoughtfully weighed the pros and cons of rationing. He characterized the pros this way: “How can it honestly be said of [the market] that it selects out and fulfills real needs when awards are being made as much on the basis of income as anything else? One fair way to make sure that everyone has an equal chance to satisfy his wants would be to give more or less the same share to each consumer independent of his budget size.”

Much later, in the 2000s, Weitzman studied the economics of climate mitigation. By the time I corresponded with him in 2011, he had little to say about rationing as part of climate policy. He wrote to me that “generally speaking, most economists, myself included, think that rationing is inferior to raising prices for ordinary goods. It can work for a limited time on patriotic appeal, say during wartime. but without this aspect, people find a way around the rationing.”

Views on rationing similar to Rockoff’s and Weitzman’s form a broad consensus among economists today, and those perspectives enjoy near-unanimous acceptance in society at large as well. In the past year or so, however, as climate projections become more dire by the day, I have noticed increased interest in rationing among academics, scientists, the general public, and even a few public officials. The well-known NASA climate scientist and activist Peter Kalmus, for instance, is now endorsing a direct phase-out of fossil fuels, supported by planned allocation and rationing, and he is drawing support.

One more example: At a committee hearing held by Ireland’s top legislative body earlier this year, four prominent climate researchers responded to committee members’ questions with blunt, urgent policy recommendations of a sort rarely, if ever, heard from scientists. One of them, Barry McMullin of Dublin City University, declared that it is time for “politically risky … leadership,” because “the scale and urgency of our predicament” requires consideration of policies “outside our previously self-imposed restrictions on what is thinkable”. That, he explained, requires rationing of energy “in a particular way that protects fairness and justice in the short term.” With rationing, “You don’t tell people how to do this. You leave it up to people to have the freedom to figure out how to best pursue their goals.” The other scientists made similarly urgent appeals, and members of the committee responded positively.

Maybe it will be the smaller industrialized nations who lead the way in establishing and respecting ecological limits. Ireland, for example, has joined Denmark, Costa Rica, France, Sweden, New Zealand, Portugal, Greenland, Wales, Quebec, and the state of California in the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance. These nations and sub-national regions have declared that they are “working together to facilitate the managed phase-out of oil and gas production.”

Sadly, we are hearing no such language in America’s political mainstream today. And prospects for action in the near future are not good. But if we and what’s left of our republic can manage to pull out of our current anti-democratic nosedive and rise to become for the first time a true multiracial, pluralistic democracy, maybe we can humbly join these smaller, wiser nations in a global effort to finally rein in our abuse of the Earth.

* The most apt historical precedent for governance of rationing was wartime U.S. National price limits on goods and ration quantities were set by the federal Office of Price Administration. Management of the system in communities, on the other hand, was carried out by approximately 5,600 local rationing boards. OPA entitled every household in the country to an equal, standard ration of essential goods; in addition, consumers could apply to the local board for supplemental rations of some of those goods. Distribution of standard ration coupons, as well as allocation of supplemental rations to applicants who could demonstrate the greatest need, was carried out by the local boards.

Board members were volunteers. They were guided by a constantly updated “loose-leaf manual” of regulations from the national rationing office, but as long as they did not exceed their federally assigned monthly quotas, they enjoyed a high degree of discretion in responding to applications. Indeed, one observer wrote that boards could be “as much influenced by non-legal circumstances as a jury in a negligence case.” When applicants were dissatisfied with decisions, the strict quotas handed down from Washington provided board members with a degree of cover; they could say, “We’re sorry, but we just haven’t been allotted enough this month for you to get extra coupons.” This was essential to the boards’ gaining broad if sometimes grudging acceptance of the restraints under which society was obliged to operate at the time.